Unceded Land

As is the case through much of British Columbia, the Summerland District was never formally surrendered by the local First Nation through an official treaty. The fertile land around Summerland was very attractive to European newcomers, and a series of laws and practices gradually moved that land to settler ownership and control.

Initial Contact

The Okanagan people traditionally occupied an area of over 69,000 square kilometers, stretching north to present-day Revelstoke and south into Washington State; however, these boundaries often fluctuated. The Okanagans first interacted with European people through the fur trade, primarily through the selling and trading of horses. The discovery of gold in the Fraser Canyon in 1857 prompted an influx of newcomers, mostly Americans, who in subsequent years steadily moved through the valleys of British Columbia. In the Okanagan Valley, pressure began to grow on colonial authorities from settlers who wanted to acquire rights to the fertile land from local First Nations groups.

Oral Agreements

In 1861, an oral agreement was made between the High Chief of the Okanagan and James Douglas, the first Governor of British Columbia, permitting the local Indigenous people to mark off a large informal reserve at the south end of Okanagan Lake. The land was surveyed according to instruction of the local people to include areas they had an interest in, including villages, agricultural land, and sacred areas, such as burial grounds. The area around Summerland was included in this informal reserve. The agreement was not a formal treaty and did not surrender First Nations ownership or resource rights to lands outside of these “reserve lands.” The goal was to make land available for First Nations people to support themselves and to open the rest of the land to settlement by both settlers and First Nations.

Reserve Decreases

The first settler pre-emption in Summerland was in Prairie Valley. This view looks west before orchards were planted, 1979-295-004

Just four years later in 1865, the subsequent political administration drastically reduced the reserve at the south end of the lake. The right for First Nations people to pre-empt (settle) on land outside of reserves was also removed a year later. Upset over decreased land rights, an Okanagan coalition of First Nations threatened war in 1877. A commission was ordered to negotiate the size of reserves, the result of which was an additional decrease to Okanagan reserve land. Government policy allocated reserve lands to First Nations based on 10 acres per family, and each First Nations family was expected to live off of those 10 acres (compared to up to 320 acres for settler families).

The commission that resulted from the threat of war also established the South Okanagan Commonage Reserve, which included the present-day Summerland District. Land was set aside for common pasturage for use by both settlers and First Nations. This allowed settlers to use that land without trespassing, but did not cede the land from the First Nations groups. A Privy Council order in 1889 opened up this land to settlement without asking or telling the Okanagan Nation.

Land Transfer of Indian Reserve #3

The flats of future downtown Summerland with James Ritchie's home in left, previously Indian Reserve #3, 1905

The majority of land around Summerland is not subject to any treaty; however, there is a dispute over the history of a relatively small, 320 acre portion of land on the flats where the downtown core is now located. This land was set aside before major settlement as Indian Reserve Number Three, and it was inhabited by the Antoine Pierre family, an Indigenous family who were members of the Okanagan Nation.

In 1904, settler James Ritchie offered the Pierre family 350 acres of land to the west for cattle grazing in exchange for the 320 acres on the flats. A Document of Release was completed between the parties, including a list of about twenty very similar looking “X’s” representing the signatures of Indian band members. A copy of the deed was signed almost a year later by the Superintendent General of Indian Affairs. A fee of one dollar was also reportedly paid.

Will Ritchie and Johnny Pierre, c.1911, 1995-009-001

The presence of a document with signatures from both band members and a federal representative leads to the argument that this transfer of land constituted a formal treaty. This argument is supported by the fact that individual parties involved in the exchange (the Pierre (First Nation) family and the Ritchie (settler) family) were reportedly both content with the deal, and the two families continued to have a positive relationship.

Unfortunately, the satisfaction of the individual parties involved have no bearing on the legal title of the land, and the treaty process is much more complicated than obtaining a document with the appropriate signatures. To understand this, it is important to understand a bit of legal history.

Going back to 1763, the King of England declared that all land in North America not already ceded or purchased was to be reserved for Aboriginal groups. The King also prohibited any private citizens from taking ownership of private lands without these lands being negotiated through the Crown. Any lands that an Aboriginal group wanted to dispose of could only be purchased by the Crown, and the agreement had to be negotiated at a public meeting between a representative of the Crown and that First Nation.

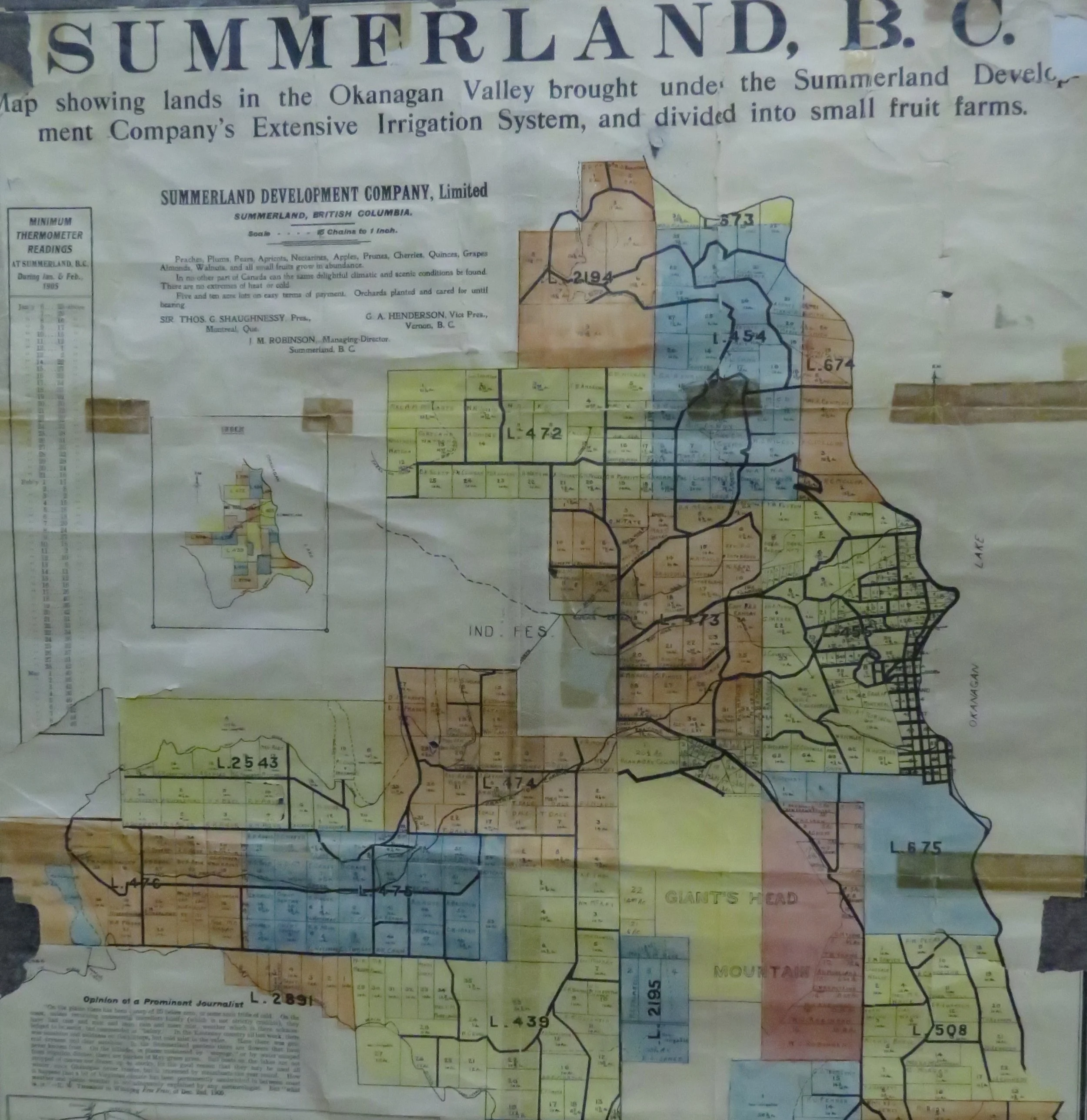

Map of the area in 1905, with the Indian Reserve shown, 1972-005

In the case of Indian Reserve No. 3 in Summerland, the final document (with signatures from the First Nation and the Crown) seems to indicate a formal treaty; however, the correct procedures were not followed. Treaties involve groups as opposed to individuals, and the original agreement was made between individual settlers and members of the First Nation (the Ritchies and the Pierres), and it was only signed after the fact by a representative of the Crown. As the Crown was not present at negotiations, and as it is unclear whether the entire Okanagan Nation was represented, the papers do not constitute a formal treaty.

Struggle for Land Ownership

First Nations groups in British Columbia, including the Okanagan First Nation, have been fighting for a voice since the 1870s. From 1906 to 1916, interior Nations sent petitions and numerous declarations to governments in Victoria, Ottawa, and London, England regarding land ownership and their rights. In 1916, various groups formed a political organization called the Allied Tribes of British Columbia (ATBC) to lobby the federal and provincial governments for additional reserve land and treaties. Realizing over time that lobbying was ineffective, the ATBC threatened litigation to address land rights, hoping that by raising their demands in court they would have a more fair and objective hearing. In 1927, the federal government made it a criminal offence for a First Nation to hire a lawyer to pursue land claims settlements (this was in place until 1951).

Treaty Rights

More recently, the Supreme Court of Canada decided in the 1984 case Guerin v The Queen that Aboriginal peoples’ legal right to the land was created not from the Royal Proclamation of 1763 (see above) but from historic occupation and possession of the land. In other words, Aboriginal peoples have a valid legal right to traditional lands not subject to Crown treaties. A further Supreme Court decision established that Aboriginal rights, including the right to use and occupy land and natural resources and to preserve languages and cultural practices, could only be extinguished through a treaty with the Crown. If a treaty does not specifically refer to certain rights being extinguished, it should be assumed that these rights continue to exist.

In 1987, the Okanagan Declaration was made stating, "Our Okanagan governments have allowed us to share equally in the resources of our mother; we have never given up our rights to our mother, our mother's resources, our governments and our religion."

As is the case in much of British Columbia, the Summerland District remains traditional unceded territory of the local First Nation; in this case, the Syilx speaking people of the Okanagan First Nation. As part of the Summerland District, the Summerland Museum respectfully acknowledges that we are situated on the unceded and ancestral territory of the Syilx people.

Further Questions

Treaty rights are often a difficult issue to approach or examine. Below are some questions we still have regarding the land transfer of Indian Reserve No. 3.

1. Why was there so much effort made to get a signed document transferring land title of Indian Reserve No. 3 to settlers when the rest of the Summerland District was never subject to a formal treaty?

2. How legal is an agreement that offers land never ceded by the First Nation (the 350 acres offered in trade) in exchange for that First Nation to actually cede a piece of land?

3. The treaty process requires agreement from the local Aboriginal community, in this case the Penticton Indian Band. Do the signatures (X's) on the document represent the majority of male members of the Penticton Indian Band?

4. Does the monetary purchase (or trade) for a piece of land extinguish a First Nations' traditional rights to that land?

5. What other issues might the Penticton Indian Band have been faced with during the period when the land transfer was made?

A Brief Timeline

1763 - Royal Proclamation made, confirming First Nations land rights

1857 - Gold discovered in the Fraser Canyon

1858 - Mainland of British Columbia declared a colony

1861 - Oral agreement made to establish reserve on the south end of Okanagan Lake

1865 - Reserve lands drastically reduced

1866 - First Nations right to pre-empt land removed

1877 - Okanagan coalition threatens war

1884 - Residential schools are legalized

1889 - Notice that land formerly set aside for pasturage open for pre-emption

1904 - Agreement between James Ritchie and Antoine Pierre transferring Indian Reserve #3

1905 - A copy of deed for the Indian Reserve #3 land exchange is signed by the Superintendent General of Indian Affairs

1910 - Chiefs appeal to Prime Minister Laurier for treaty redress to define their rights

1912 - Interior tribes petition Prime Minister Bordon regarding ownership of lands

1916 - Allied Tribes of British Columbia formed to lobby federal and provincial governments for additional reserve lands and treaties.

1927 - Federal government makes it a criminal offence for First Nations to hire a lawyer to pursue land claims

1973 - Supreme Court finds that basic principles of the Royal Proclamation are generally applicable in B.C.

1984 - Supreme Court Guerin v The Queen found legal right to land from historic occupation of land

1987 - Okanagan Declaration made