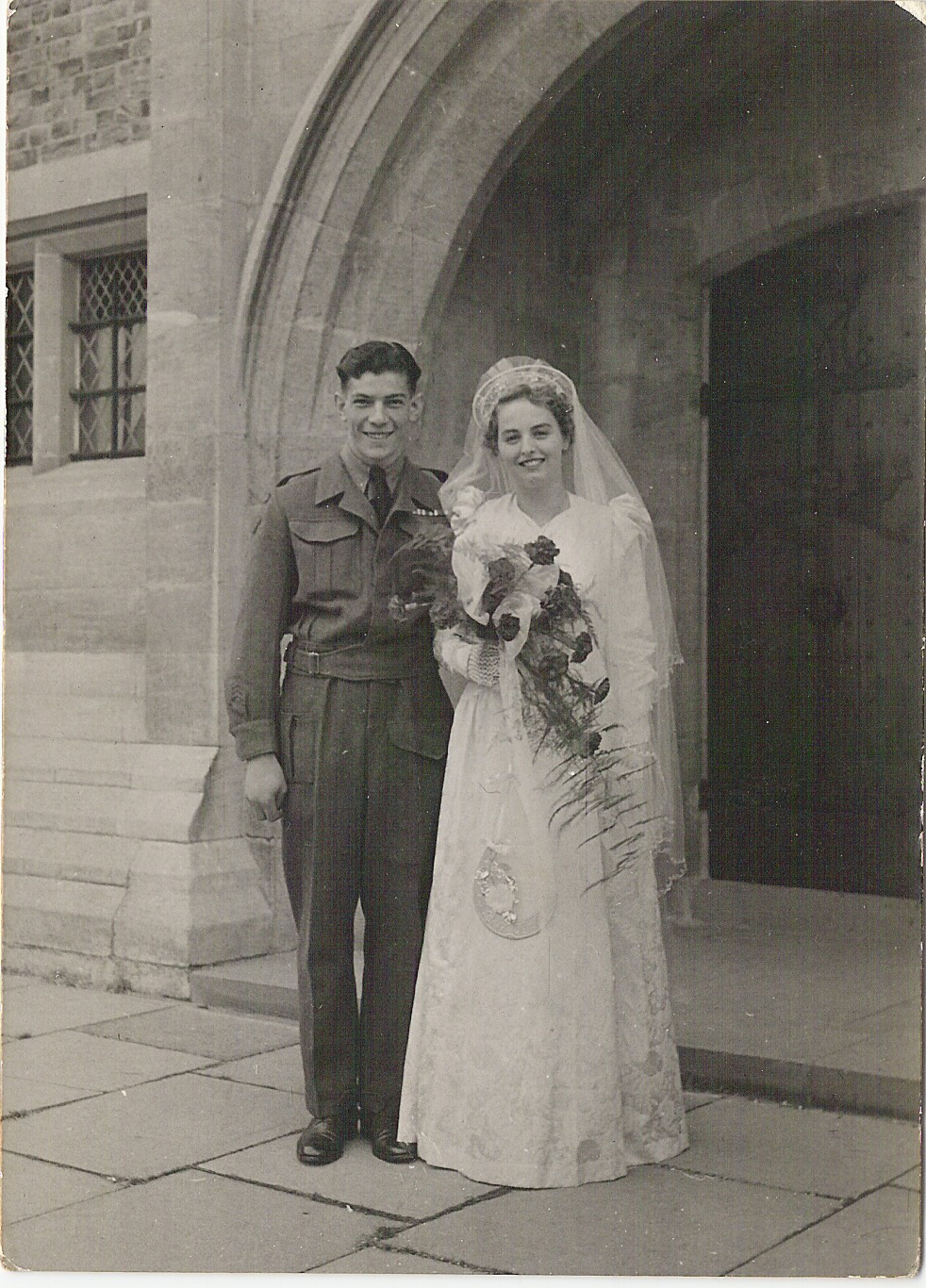

c. 1945. Olive Danyluk and her husband Mike on their wedding day in England during WWII.

On November 24, 2018, the Summerland Museum and the Summerland Legion Branch 22 hosted a presentation on Summerland’s war brides. The Summerland Museum received a generous donation and sponsorship from the Legion to host this event. Speakers included John Dorn, Kay Fenwick Treadgold, and war brides Enid Dorn and Doiran Blagborne Thomson. Transcripts from this event are offered here. We would also like to thank volunteers Carol Stathers, Ruthie Charles, and Sherri Macdonald for their help with this event. For further information on Canadian war brides, check out this short and entertaining video HERE.

c. April 27, 1987. A group of local war brides gathered in Marjorie Lane’s garden. Front: Stevie Ross, Mary Coates, Amy Lamb, Kathy Davidson, Olive Danyluk, Kay Agur; second row: Marjorie Lane, Jo Callan, Hilda Hornseth, Mima Laidlaw; third row: Gwen Seifert, Elizabeth Watt, Enid Dorn, Nora Aten; back row: Grace Quanstrom, Rose Bruce, Olive King, Doris Hancock, Hilda Pickerkel, Diana Rippley, Ida Grahn

JOHN DORN OF THE SUMMERLAND LEGION:

“I am here today with my war bride mother Enid, 93 years of age.

The term “war bride” refers to young women, mostly from Britain, who married Canadian servicemen during the Second World War. Immigration Branch statistics state that 65,000 soldiers’ dependents, consisting of 44,000 brides and 21,000 children, were brought to Canada. They are responsible for over a million descendants like me.The Canadian Army issued a directive regarding marriage in foreign lands. It said “marriage with a person of a different country, particularly by young soldiers, where there is a difference of religion, is open to obvious risks of future unhappiness. Commanding officers are instructed to refuse consent outright if they were “not satisfied that a reasonable basis for a happy marriage existed and in any event a four months’ waiting period will be imposed between the date of the granting of permission to marry and the wedding, unless there are circumstances [such as pregnancy] making the delay undesirable or unnecessary.”

Young people, used to the hardships of war, saw few good reasons to wait. Many young women in Britain had already faced nightly bombing raids, the deaths of family members or friends, blackouts, and rationing. For the young Canadian servicemen, the order to ship out to battle on a moment’s notice was expected daily. Life was for living.

High Commissioner to London, Vincent Massey, recommended to the Department of External Affairs that empty troop ships returning to Canada should also transport war brides and their children. Massey suggested that each adult would pay fifteen dollars to provide for their own meals, while the Canadian government would charter the ships and pay for each traveller’s passage, an average cost of $140.29.

Military Headquarters objected to the free repatriation of the war brides and children on the grounds that there were “too many irresponsible marriages taking place.”

In the display case is a letter from the Department of Mines and Resources to my father’s father. It is quite intrusive, demanding to know his income, size of house, and other circumstances before permission would be granted for my mum to come to Canada.

Most war brides arrived at Pier 21 in Halifax and then took special war bride trains bound for various points across Canada. If you are ever in Halifax, you should tour the Pier 21 museum. Their virtual train ride across Canada is something you would not want to miss. The Pier 21 website is very informative and staff and volunteers will search records for details of immigrants’ arrivals.

We believe four war brides married chaps from Summerland. During the 1980s and 90s, the war brides would get together socially. The plaque on the Summerland Legion fireplace notes the names of 43 women who eventually settled here, of whom six are still alive in town.”

War Bride Enid Dorn:

“I lived in Ipswich on the east coast of England with my parents. I was working at a retail store called Hewitt’s Fine Grocery as assistant behind the counter. Later on, I was a “clippie” on the busses as it paid a bit more. My bicycle got me back and forth to work.

During the war, we had to make sure the house windows had black-out curtains. There were constant air raid warnings. We had an Anderson shelter in the back yard to take refuge in when the air raid sirens were sounding. We each had a ration card. One got one egg a week if you were lucky. Never any sweets or treats. Two ounces of butter, maybe four ounces of lard, and milk were all rationed.

One day, my mum lucked into a queue and bought two pounds of sprats, which were a treat. My dad saw the same queue, and he bought his allotment of two pounds as well. I later on did the same thing. We were stuck with all these fish and no refrigeration. The neighbours helped us out by feasting on the sprats.

The family moved to Shrewsbury with an aunt and uncle. My mum got fed up with that after a while and said “if we are going to die, so be it,” so we moved back to Ipswich. My younger brother, Terry, was evacuated to a boarding school in the country where it was safer. He would have been about 8 years old at the time and stayed for the duration of the war.

My Aunt Ida had invited a Canadian soldier and his friend to tea with me. The friend was assigned guard duty and was unable to get leave. As a result, my future husband Roland took the friend’s place.

Roland and I were married in April 1943. Eleanor Roosevelt had a program to donate wedding dresses in Britain. A bride had the loan of the dress with the provision of dry cleaning the dress afterwards at the cost of ten shillings. I had to scrounge around for ration coupons for the wedding reception and to purchase my ‘going away’ clothing. We took the train to Scotland for our honeymoon.

In 1946, I received a telegram detailing arrangements for travel to Canada. My mum gave me a substantial bundle of cash in case things did not work out and I wanted to come home. I took a train to London, then on to Southampton. We boarded an ex-troopship, the ‘Aquitania.’ I was assigned an upper bunk in the hold with hundreds of other war brides and some children. The food was exceptional compared to what was available in England. Everyone was excited about the white bread, which we had not seen for a long time. There were children who had never seen fruit such as a banana before.

When we arrived in Halifax at Pier 21, we had to wait for hours for the new Governor General, Viscount Alexander, to disembark as the carpet and brass band we not organized.

I took a train the next day to my new home in Yorkton, Saskatchewan. I was not used to outdoor toilets or cooking on a wood stove. Milking cows and collecting eggs was a novelty.

My husband had planned to become a carpenter using his father’s tools. His mother had sold the tools while the boys were overseas. Roland instead went to university and became a professional engineer. The government paid for his education, so it turned out for the best. My parents and brother followed me to Canada a few years later.

I have two sons and now five grandchildren and one great granddaughter.”

War Bride Doiran Blagborne Thomson:

c. 1944. Wedding photo of Bruce Blagborne and Doiran Phillips.

“I grew up in Ipswich, located on the lower east of the United Kingdom about 12-15 miles from the North Sea and at the head of the River Orwell. It is the land of ‘the big sky’ and Constable, the famous painter. Historically, the River Orwell was a trade route from the North Sea, but before that, it served the Vikings from across the water as an access to the community, and their visit left the area where I grew up populated with redheads! Of significance to our history is the location of the Sutton Hoo burial grounds from the 7th and 8th centuries, which upon excavation, bore a strong resemblance to Swedish burial grounds and related verbally to the old poem Beowolf.

My mother was one of thirteen children and my father one of seven. I had numerous aunts, uncles, and cousins in Ipswich, and I have carried the sense of security it gave me all my life. I was the eldest of two daughters. When WW2 was declared, my sister, who was three years younger than me, was evacuated with her school to the interior of Britain as the possibility of invasion became a strong possibility. My parents sent me to Miss Hazel’s Business College where I learned Pitman’s Shorthand and Typing.

Everyone had to contribute to the war effort, and my mother began working for the Ministry of Food five days a week. My father was a part-time officer in the Youth Air Training Corps and worked evenings and weekends training teenage boys for entry into flying school in the RAF. When I was seventeen, I applied to ATS, the army representation of the three services. How that one step changed my whole life. I was sent to a school in Golder’s Green, located close to London, and given special training to transfer me to a new life in Bulford, Salisbury Plain, working with Staff Officers who were planning the invasion that eventually took place on D Day.

Salisbury Plain was a training ground for the army and especially for the new branch of parachutists and glider transportation for ground troops. The 1st and 6th British Airborne Divisions were located in Bulford, and the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion was attached to the 6th Airborne Division.

I met my husband, who was a Sergeant in the 1st Canadian Battalion, at a dance at the old Bulford gymnasium in February 1944. He was so different to anyone I had met before. We walked all over Salisbury Plain when our days off coincided. He talked a lot about the Okanagan: the orchards; the hunting; the fishing; the summers and winters; and how difficult it was to find year-round employment if you didn’t have a trade.

He went into action at midnight on June 6, 1944, six hours before D Day started, and I didn’t hear from him again for three weeks when his first letter from action in France arrived. He had been taken prisoner and abused to obtain information for which he paid for the rest of his life. The 6th Airborne Division was returned to Salisbury Plain in September 1944 to regroup, with Bruce among them. Allocated three days leave in October, we were married in Ipswich with two of his friends there to support him. It was originally scheduled for October 14th, but it had to be postponed to the 19th as permission from his Commanding Officer did not come through in time. I had to be investigated!

My large family got together and all donated clothing coupons so I could have a white wedding with four bridesmaids and one flower girl. My ‘going away’ dress was also obtained that way and was of red velvet with a fur fabric coat over it. Wow! My mother made me a bountiful nightdress out of parachute silk, which Bruce had given me. Bruce and I travelled by train to Woking, in Surrey, which was on the way back to Salisbury Plain. Once in Bulford, we separated to our different units. Very soon, Bruce was sent to the Royal Military College, also known as Sandhurst. He was one of the first four Canadians to graduate from Sandhurst with a Commission, and after months apart, I was now married to a Lieutenant.

Bruce was eventually sent back to Canada because of the effect of being a prisoner, and I was left in Ipswich to have my first son.

When Roger was three months old, I was informed I had a berth on the Queen Mary I, and I sailed to Canada at the beginning of August 1946. A foggy, gently rocking ride, with wonderful food, we docked at Pier 21 where we were met by a brass band playing ‘Here Comes the Bride.’ A bride you say. Some girls were pregnant. Some, like me, had one child, while some had three! Those Canadian boys were much like those early Vikings that sailed up the River Orwell to Ipswich!

I loved the train with its beautiful wood panelling on the walls and ceiling, but everything was so big! The engine—sometimes two of them—were so intimidating as they hissed and steamed at railway stations in what looked like the middle of nowhere. Stops across Canada were traumatic experiences as I saw war brides getting off at whistle stops in what appeared to be the middle of nowhere. Some brides had not hear from their husbands since leaving their home, although most of us received telegrams from them. For those with no ‘reaching out’ from their husbands or their husbands’ families, the ladies of the Red Cross, who were always there for us from the time we left England, took over their care. So terribly sad was the feeling of being lost in this huge, beautiful wide country.

At Calgary, I had to change trains to come via the Crow’s Nest Pass to Penticton. So close on the map but so far in reality. It was daytime, August, and the scenery was wonderful—especially at Nelson where the Kootenay Lake lay sparkling and deep blue in the midday sunshine.

I arrived at Penticton Railway Station at 3 a.m. in the morning after watching from the zigzagging train all the way from the top of Okanagan Mountain. Roger developed diarrhea and I had put the last clean diaper on him close to our destination. But guess what? I found Bruce and his brother, Ken, waiting for us, but Bruce had just cut off the tips of his fingers on his right hand, so it was Ken who took my smelly little bundle while Bruce could only look the first time he met his son!

We lived with Ken and Naomi for three months until we bought a shell of a house in the Parkdale District, which Bruce finished over time. A front door, a back door, a toilet, and a wash basin. No bath. Brown paper on the floors. That was post-war Canada for a lot of people. My kitchen stove was wood fired, and we used fast-burning box wood from the Box Factory that was located in what is now the industrial site, which was called James Lake then. It cooked quickly, but it made the house so hot. I also had a pot-bellied stove, which was huge in the living room, and it was a hungry beast that went through a cord of slab wood in nothing flat! But my radio! How I loved it, as the Canada-wide programming was interesting and at times fun. The music on Saturday nights kept us entertained when we didn’t have a car.

I found the women of Summerland incredibly resourceful and hardworking. They had had to manage without men: looking after the orchard; working at the packing houses and canneries; raising their families; and canning meats, fruits, and vegetables. They were generous with their knowledge after word came to them that I was helpless! I really wanted to do all the things they were doing, especially make bread.

I loved Summerland. The Canadian Legion ladies hosted a shower for the war brides, including Ilene Blagborne, Sylvia Penny, Magna Fenwick, and Mrs. Reid. Several of them told us they had been WWI brides.

Mima Laidlaw came a little later, about 1948 or 1949 I think, after Bill returned to Scotland to marry her. She joined us with forming two Brownie packs and one large Girl Guide Company with 60 girls. Each of six patrols took the name of a flower or a bird, but we were restricted to what kind of embroidered emblem we could get for their uniform. Unfortunately, we Brits recommended the Blue Tit of the birds for a patrol name, which was the cause of much hilarity among the Canadian girls each time we called out that name! We had to change it!

Back then, Summerland had orchards everywhere. The income was very limited, and the small shopping centre had little choice. But, it did have a library and an incredibly active Chamber of Commerce, where I heard Dr. Andrew (who is now very senior) talk about coming to Summerland when he married. There were Gilbert and Sullivan presentations with talented individuals and Anglican, United, Baptist, and Catholic churches. The hospital was entirely supported by donations and provided for by an active hospital auxiliary. There wasn’t a mayor, but someone called a “Reeve,” and a railway station. And I never saw a policeman!

One difference between Ipswich and Summerland was that Ipswich had lots of policemen! Like Summerland, Ipswich had hardworking women during WWII, but it was in a different way. The big sky in Ipswich could not be compared to the closed-in venue of Garnett Valley, where I first lived, but I loved all of it (including the mailboxes that have since changed).”